As I recently defended my thesis, and since I am now looking for a job, I decided to dedicate to myself some time to study cutting edge computer science topics. Deep learning is one very famous (and somehow controversial) topic that I didn’t have the occasion to experiment with so far. Thus I started playing with dl frameworks such as pytorch and recently I decided to implement an old idea that I had back during my thesis: inducing the rules of chess using a machine learning algorithm.

To be clear, the goal here is not to create an algorithm able to play chess such as alphago, but rather to create an algorithm able to discover the rules, and able to propose the next moves from a given board configuration. I got this idea from my PhD work on inductive logic programming, a form of machine learning applied to logical models. For example, imagine that you are looking at two people playing an unknown game: is it possible to understand the rules just by looking people play ?

Introduction

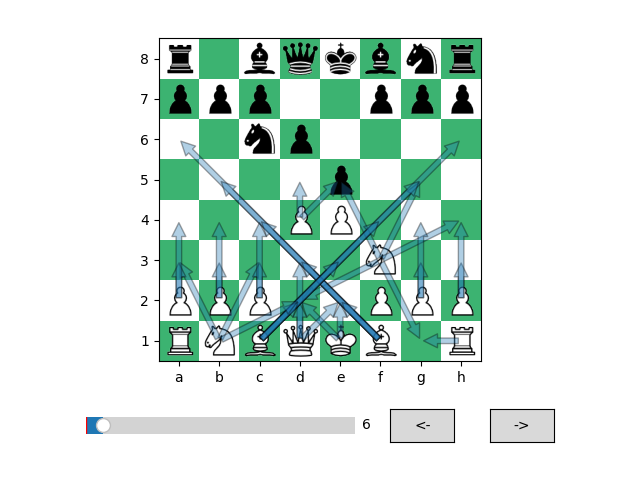

For this project, I decided to use the deep learning framework pytorch. I started by creating a python program that is able to show a board in different configurations using matplotlib with these images. I used the very nice python-chess package as a chess engine to simplify the work. With these elements, I was already able to visualize all the board configuration form a given game, with the possible moves for each piece (see below).

The chess interface.

The dataset

Since I needed a dataset for this project, I used this csv of chess games, where the games are given in the form of lists of moves (easy to process with python-chess).

At this stage, I decided to simplify the learning task because predicting the possible (legal) moves from a board configuration implies using a model with a varying output size, something difficult to achieve with deep neural nets. I choose to simplify the problem by predicting only the possible destinations for a given pieces, ignoring the interaction with the other pieces (which is quite cheating considering the initial idea, but interesting as a first step). I made a second simplification assuming that all the possible moves from the board position are known (which is not the case in my previous description since only one possible move can be seen when someone plays).

Fetching the model inputs/outputs

In order to obtain a usable dataset for fitting the model, I generated all the board configurations from the moves of all the games in the csv. I then generated all the possible moves from these configurations and I subsampled the data to limit its size.

Encoding the data

A very important aspect of a deep learning application is the encoding of the data. More precisely, neural networks would not be able to process high level information such as a list of moves and a board configuration with piece types. For this reason, it is necessary to encode the data in such a way that the model will be able to link the input and the output through its complex computations. For instance, coding the piece type on the board with an integer won’t be efficient since it would be too difficult for the model to decompose the integer.

Encoding the input

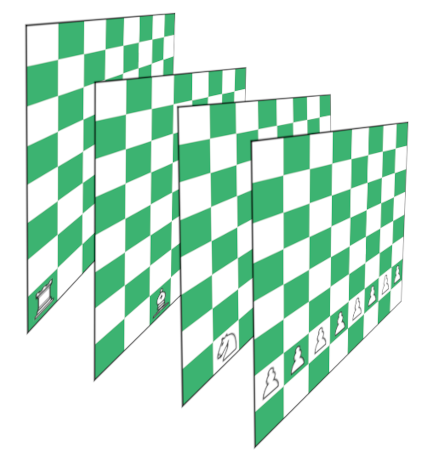

In our case, the input consists in a board configuration plus a piece to move. An important aspect of chess is that the board is two-dimensional. This means that the moves of one piece depend on the content of its surrounding squares. For this reason, we are going to use convolutional layers for the model architecture, a type of function that is efficient for treating spatial data such as images (more on the model architecture below). This implies that the encoding should conserve the spatial organisation of the board (with two dimensional data structures).

The input of the model is the hardest element to encode. As I said previously, piece types cannot be encoded as simple numbers, as they represent categorical variables. One popular way to encode categorical variables in deep learning is the one hot encoding, consisting in a vector of 0 and 1, with only one index equal to one depending on the class that is coded. Our encoding here will be based on same principle, inspired from the encoding used in existing chess AI’s (including the alphazero model). The categorical input will be implemented as a spatial dimension of the board in order to help the model consider several piece types at the same time. Thus, the final encoding of a board will be a 3d array, where the depth dimension (depth = 2*6) represents the type of piece. By doing so, the model will be able to perform computations involving different types of pieces at the same time. You can visualize the idea of the board encoding on the figure below, where the first board layers have been shown for the white pieces.

Additionally to the board, we will also represent as input the piece to move. This will be encoded as a two dimensional 0/1 8x8 array, where the unique value 1 corresponds to the piece to move. At the end, the input is a 3 dimensional array containing 8x8x(6+6+1) = 832 values. This seems expensive but this representation is really important for the model.

Encoding the output

Our model output consists in all the possible moves for the piece given as input. Since we are not considering encoding information such as piece capture, the output will simply consist of a 0/1 8x8 array with a 1 value for each possible destination of the piece.

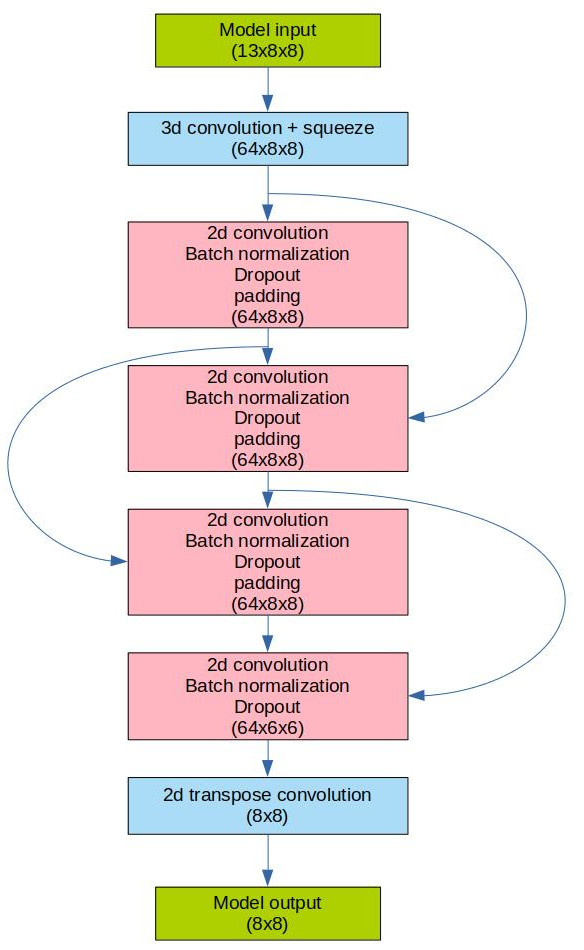

Creating the model architecture

The model architecture is another crucial step here. Once again, I took inspiration from existing models such as alphazero for this design. The first layer is a 3d convolutional layer applied to the input, with a kernel size equal to 13x3x3 so that all the depth layers are considered. After that, the model contains 4 successive 2d convolutional modules, with a convolutional layer, a batch normalization layer and a zero padding layer. This way, all the intermediate inputs are 8*8 arrays, and I also introduced residual connections between the these modules. Finally, there are two transposed convolutional layers to obtain a final 8x8 output.

Testing the model

Once the architecture is decided, it is time to fit the model on our dataset. In this case, I used the cross entropy loss function which is usually applied to classification problems. I then used the default stochastic gradient descent algorithm for the optimization of the model, with a batch size equal to 150.

Model training

Training the model was a little bit fastidious due to some bugs in the input encoding. I finally obtained a working version achieving an accuracy of 97% on the test set, which is quite satisfying (the accuracy was computed as the number of correct values in the output). I experimented with several parameters such as the number of outputs in the convolutional layers, the loss function, the optimization algorithm, and so on… Initially, the dataset was composed of only the boards from the first games of the csv files, but I realized that it was not diverse enough since a board configuration would not evolve much from few moves For the other parameters, I did not find any big differences between the trainings.

Model testing

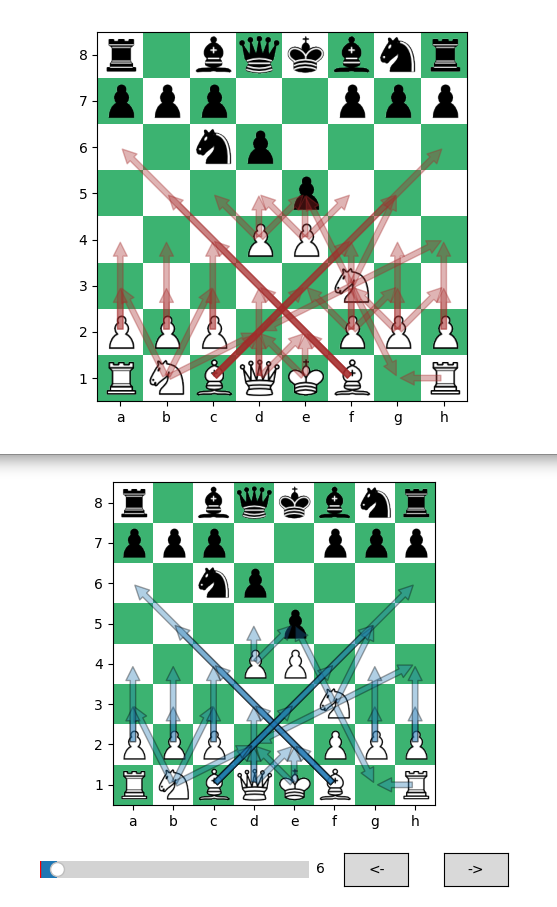

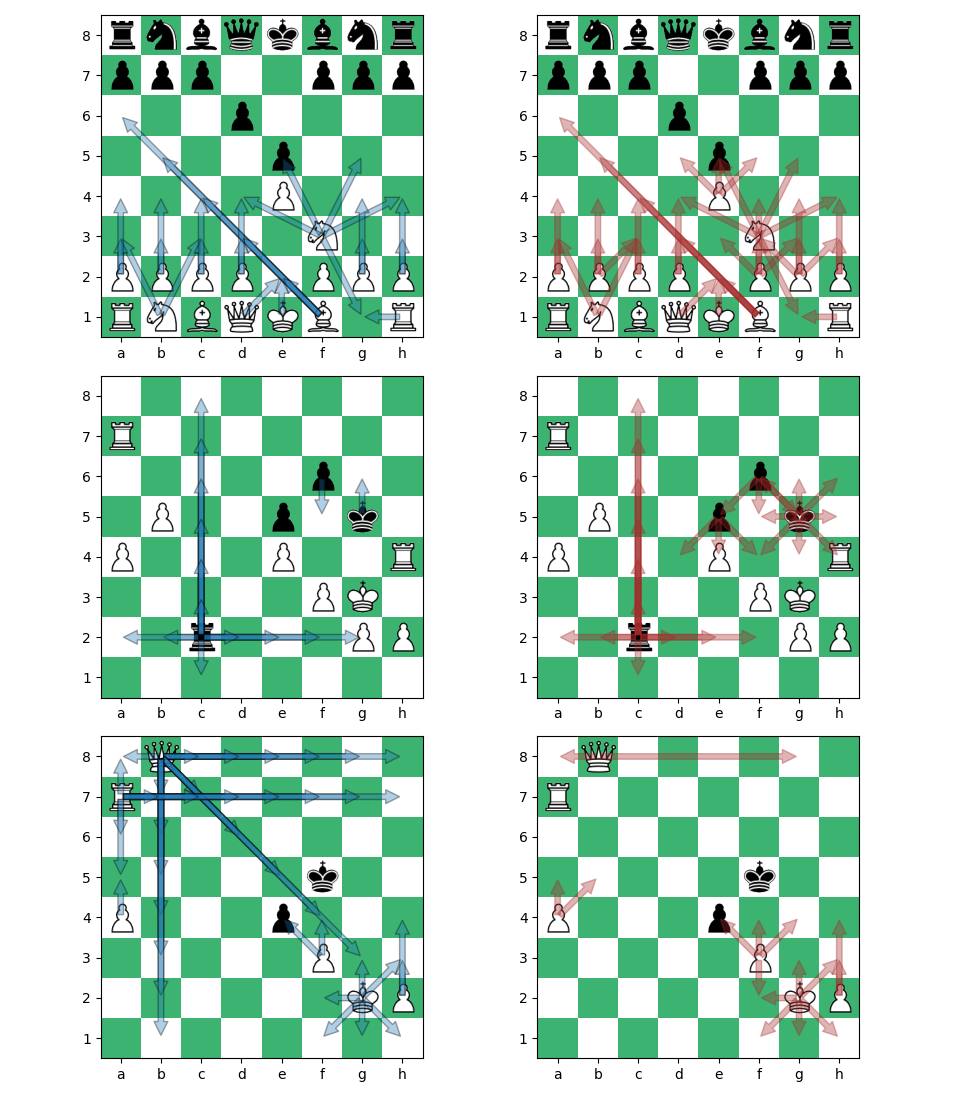

For testing the trained model, I selected a game and plotted both the moves proposed from the rules (blue arrows) and the moves proposed by the deep neural network (red arrows). You can find a first comparison on the image below. The result is quite satisfying, although it is not perfect. It really gives the impression that the model learnt something, and that it is able to generalize on the data.

Observations

You will find below few board comparisons from one particular game. It is interesting to notice several particularities. For instance the model allows pawns to move diagonally, which has been probably inferred from the captures. The moves from the rooks are partially well predicted, but these seem difficult to compute We can also see that illegal moves are not managed at all by the model.

Conclusion

To conclude on this deep learning application, I find it interesting to see the good accuracy of the model at the end, and I am confident that the model can be further improved. It will be for instance interesting to find a way to encode the capture and to infer the rules only from the moves of a set of games (instead of using the rules to generate all the moves each time). Although this particular application does not seem to be really practically useful, it is still interesting to see what these models are capable of. I personally find it fascinating that deep learning models are somehow able to make sense of very complex patterns such as board configurations. This latter point was already shown by the unreasonable efficiency of the alphago model for the game of go. Indeed, looking for the best move for a board game was a problem traditionally treated with tree search approaches. Seeing the efficiency of neural nets makes me think we are far from understanding the possible connections between continuous models and symbolic computations.

Related works

Following this project, was curious to see if such problem has already been treated. So I searched for similar attempts online, even if my initial goal was to become more familiar with deep learning. We may compare this task to the alphazero algorithm which is able to learn playing a game board from scratch. However, this is somehow different because alphazero is not designed to output a list of moves. So we may still think that from its playing, this type of model is somehow able to understand the rules, but whether it may output them remains unclear. I found this discussion on the topic, and that one, but no other deep learning model for the rules of chess.

Source code

The source code of this project is available on github (folder chess_rules).

The code includes the assets used for the graphical interface and the trained model with the selected architecture.

Please feel free to re-use and improve the model (and let me know if you are able to improve the result and get new ideas) !